Passive Solar for Beginners

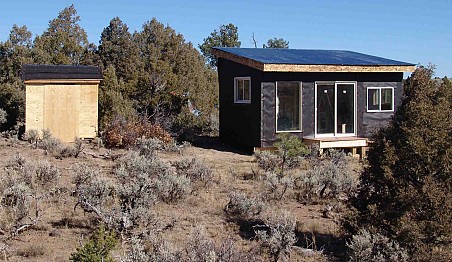

One of the benefits of living in the Wild West is our abundant sunshine. An advantage for home builders in Denver is that Colorado averages over 300 sunny days per year. My home here in Colorado is located on the north-facing side of a mountain. It's not uncommon to see snow in my yard well into May. We have some pretty sweet views of more mountains and the Continental Divide to the west and north of us, but not much potential for passive solar heating. However, when I designed and built our small sunny cabin in New Mexico, a primary design consideration was to provide some passive solar heating.

One of the benefits of living in the Wild West is our abundant sunshine. An advantage for home builders in Denver is that Colorado averages over 300 sunny days per year. My home here in Colorado is located on the north-facing side of a mountain. It's not uncommon to see snow in my yard well into May. We have some pretty sweet views of more mountains and the Continental Divide to the west and north of us, but not much potential for passive solar heating. However, when I designed and built our small sunny cabin in New Mexico, a primary design consideration was to provide some passive solar heating.

What is Passive Solar?

Passive solar is pretty simple: The solar part is obvious…it refers to the Sun. The passive part means the system works without any mechanical devices, added energy inputs, or effort from the occupants. The home basically heats itself by smart design.

Anyone who has ever left their car sitting in the hot summer sun knows all too well that windows allow sunshine to enter and warm the inside. In a vehicle, these temperatures can reach 150° F or more very quickly. A concentrated version of this same phenomenon allows solar ovens to bake and cook foods at 350° F to 400° F.

Practical Considerations

When it comes to using this type of system to heat your home, you'll need to address 4 important considerations:

- Site location: For starters, you’re going to need some sun. Having a home located deep in a dense pine forest will not work too well. Similarly with steep canyons and hillsides, the quantity of sun that "lands" on the property directly relates to how effectively it can be harnessed. In urban areas, large neighboring buildings may block sunlight, restricting or preventing good passive solar designs.

- Orientation: Another design constraint is that you must point your solar collectors (a.k.a. "windows") toward the sun. In the northern hemisphere, this direction is south. A home with a large glazed southern exposure and minimal northern glazing is the basis for practical design.

- Thermal Mass: All this sun energy needs to be stored or moderated, which is best done with heat-and energy-absorbing components.

- Seasonal Shading: This is the trickiest part. You want the sun to work for you in the cool months when it provides needed warmth, but not in summer when you don't need it.

When solar designs were first being developed, there was a common idea that the more windows you had, the better off you were. This design led to homes that would get smoking hot when the sun was shining but then turn wickedly cool once the sun went down. Others would just be baking hot all summer long. These homes were missing the critical thermal mass component to moderate day-to-night swings and often lacked the seasonal shading part to prevent overheating in the summer, as well.

Thermal Mass

In a passive solar design, the thermal mass element is what keeps things from swinging widely from hot to cold, during a typical day and night cycle. An example of how it works: When you start cooking a very large pot of water, the water is cold and the stove adds heat. The pot of water "collects" the heat until it reaches a boil, and then when the heat is turned off the pot of water will remain hot for a long time. Thermal mass acts a bit like a mechanical flywheel to even out the highs and lows.

In my cabin this thermal mass is built into the tile floor. The cement backer board beneath the tile adds about 800 pounds of “mass,” while the tile, adhesives, and grout etc. contribute another 600 pounds or so. Other components add a bit more, like the granite countertop, the cast iron of the wood stove and the wall tile behind the wood stove. This tile rests over an R-30 insulated floor, which also works by keeping the storage within the thermal envelope. In ideal designs, poured concrete floors or slabs, trombe walls, water walls and other massive internal components make my tile floor’s thermal mass seem wimpy.

Earthships are a type of passive solar structure than use tons and tons of soil and concrete as their thermal mass and are common in the area of my cabin. Before the temperature in my cabin can rise too quickly, a lot of the Sun’s energy is "used up" warming the floor rather than just the air inside. When the Sun goes down, the warmth and energy stored in the floor then radiates back out keeping the room warm.

How Effective is Passive Solar?

Here's a measure of how effectively this system can work: We visited our cabin over Thanksgiving. It was a sunny but cool day for our trip. When we arrived an hour after dark, I read surface temperatures indoors and out. The exterior deck was sitting at a chilly 26°, while inside the cabin the tile floor and walls read 65°. I repeated this experiment on our New Years’ trip. That visit was not quite as sunny and much colder; those numbers were 4° and 41° respectively. 30-40° warmer seems to be a pretty average spread (inside vs. outside) when the sun is shining. This added warmth eventually dissipates overnight. Late at night and in very cloudy or snowy weather, we fire up the small wood stove to stay warm and cozy. In late fall and early spring we often get by without needing a fire at all.

Seasonal Shading

The key to successful seasonal shading has to do with the relationship of the sun’s angle above the horizon and the roof overhang atop the windows. This concept was understood and utilized in prehistoric times. Ancient Anasazi people used the same sun angle/overhang principle. They built entire clusters of dwellings in these "winter sun pockets." Mesa Verde National Park’s Cliff Palace is a fine example.

My cabin in northern New Mexico sits at 36° of latitude. During the peak of the summer, the sun is about 42° above the southern horizon. At this time of year, the roof’s overhang prevents the midday sun’s rays from entering the windows, as demonstrated in the following photo. Notice that the shadow of the eave can be seen near the bottom of the picture window/sliding doors.

During the winter months, the sun’s angle is only about 12° above the horizon. (This seasonal difference has to do with the Earth’s tilt on its axis and our annual trip around the sun.) The low solar angle allows the sunshine to enter the cabin and shine on the tile floor. In the late October photo below, you can see the shadow of the eave up at the tops of the picture window and sliding door locations. (Author's Note: This photo shows the cabin in its more rustic early build state. Keep in mind that this is a "pay as you go" remote project for us.)

We now have a number of cabin winter visits under our belts, and I am pleased to say that my design seems to be working quite well. Before we got the inside of the cabin fully insulated, we would need to stoke the wood stove quite a bit to stay comfortable. Now that job is mostly done by our nearest and dearest star…the sun. In a way you could say my cabin in heated by nuclear fusion; after all that's what keeps the sun burning away.

If you're considering passive solar installation in your home or cabin, contact a professional for expert help.

Kevin Stevens writes for Networx.

Updated July 15, 2018.

Looking for a Pro? Call us (866) 441-6648

Electrical Average Costs

Electricians Experiences

Yard Cleanup And Lawn Care Service With A Great Work Ethic

Tree Removal So Fast And Efficient It Didn’t Even Wake Our Newborn